|

|

- Search

| Arch Hand Microsurg > Epub ahead of print |

|

Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to determine whether the clinical outcomes of antegrade and retrograde extra-articular Kirschner wire (K-wire) pinning differed in proximal phalanx base fractures.

Methods

This retrospective study investigated 73 patients aged ≥18 years with extra-articular proximal phalanx base fractures that were treated by closed K-wire pinning between January 2014 and June 2023. Patients were analyzed according to whether the K-wire fixation was antegrade or retrograde. We analyzed demographics, injury characteristics, the number of K-wires applied, surgical duration, the interval before implant removal, and when physical therapy was started. Radiological outcomes included the amount of time required for radiographically confirmed bone union. Clinical outcomes consisted of complications, total active motion (TAM), and the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ).

Results

We treated 29 and 44 patients using antegrade and retrograde K-wire fixation, respectively. The overall complication rate was higher in the antegrade group than in the retrograde group (13.8% vs. 9.1%), although this difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, no significant between-group differences were detected in the length of time required for bone union and implant removal, TAM, and MHQ scores.

Fractures of the proximal phalanx consist of 23% of all hand fractures [1], which is similar to the incidence of distal phalanx fractures and followed by middle phalanx fractures [2,3]. Whether a fractured proximal phalanx is stable or unstable is crucial to determine before deciding on management strategies. Early mobilization of adjacent joints does not lead to misalignment or displacement of stable fractures, and treatment typically involves splinting with metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint (MPJ) flexion and interphalangeal joint (IPJ) extension [4]. In contrast, unstable fractures can be displaced by minimal force and require surgical intervention [4,5]. In 2011, Singh et al. [6] compared conservative and surgical management of proximal phalanx fractures, finding good results in 89% and 92% of cases, respectively. Their analysis concluded that while conservative treatment is sufficient for stable fractures, surgery is preferable for achieving better outcomes in cases of unstable fractures.

Common surgical methods for treating unstable proximal phalanx fractures include fixation with Kirschner wires (K-wires), plates and screws, as well as intramedullary screws [7]. Among these, K-wires are prevalent due to their cost-effectiveness, simplicity of application, and better aesthetic outcomes [7-9]. Another advantage of K-wires is their minimally invasive nature, which grants them superiority over other internal fixation devices in the region of the proximal phalanx base, an area covered by the extensor tendon [9]. We use extra-articular K-wire pinning to treat proximal phalanx base fractures via either a retrograde or antegrade approach based on the starting point and direction of the fixation. Our objective was to determine whether these approaches differ in terms of radiological and clinical outcomes.

Ethics statement: The Institutional Review Board of Gwangmyeong Sungae General Hospital approved the design of this study (No. KIRB-2024-N-001), which adhered to the ethical principles enshrined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 amendment). All patients provided written informed consent to the publication of this study, including all clinical images.

This retrospective review of medical records at a single institution identified 73 patients aged ≥18 years with extra-articular fractures of the proximal phalanx base that were treated by closed pinning with K-wires between January 2014 and June 2023. The exclusion criteria were as follows: open injuries; thumb, intraarticular, and concurrent fractures of the distal or middle phalanges; immature skeleton; and <12 months of follow-up. Our specific focus on the base of the proximal phalanx was due to the use of different fixator materials and open surgical procedures in other areas of the proximal phalanx [9]. The patients were classified according to whether their fractures were treated by antegrade or retrograde K-wire fixation. We then compared demographics, injury characteristics, surgical procedures, postoperative management, and outcomes. We investigated the causes of fractures and classified them as oblique, transverse, or comminuted. The surgical procedure was analyzed based on the number of K-wires applied and the surgical duration. Postoperative management included the timing of implant removal and the start of physical therapy. Outcomes were evaluated based on radiological findings and clinical outcomes.

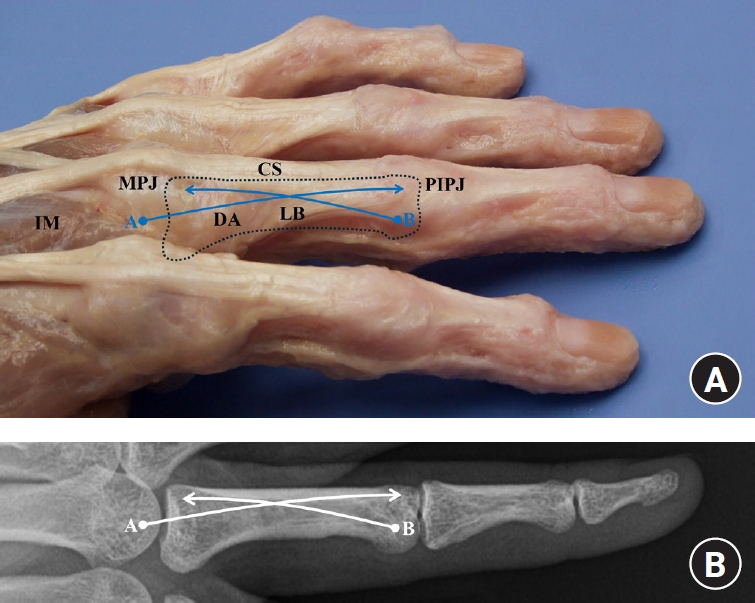

The surgeries were performed by four experienced hand surgeons from our institution, boasting an average of 22.3 years of experience. Each surgeon utilized both antegrade and retrograde fixation methods. All surgeries proceeded under brachial plexus block anesthesia, with a pneumatic tourniquet inflated on the upper arm. Fracture sites were visualized using real-time C-arm fluoroscopy. The IPJs were fully extended, and manual reduction was achieved through distal finger traction to prevent contractures of the collateral ligament and volar plate. Percutaneous closed K-wire fixation proceeded after adequate reduction was achieved. The fixation begins either at the distal or proximal part of the proximal phalanx, advancing obliquely in the opposite direction to cross the fracture site, while avoiding penetration of the articular surface. Antegrade fixation starts by passing through the extensor hood, moving from the proximal to the distal part, whereas retrograde fixation starts directly at the distal part (Fig. 1). Two K-wires were typically used for cross fixation, but a single wire was used for oblique fixation if it was sufficient to maintain stability. We used the minimum K-wire diameter of 0.9 mm required to maintain the stability of proximal phalanx fractures [5]. The K-wire is typically inserted straight, but it bends slightly after reaching the opposite cortex as it advances along the space between the cortex and medulla. The relatively thin diameter of the K-wire allows for such bending, ensuring rigidity through a compression effect on the bone structure.

Postoperative splint immobilization is applied in the intrinsic-plus position to allow MCP joint flexion. This adds tension to the collateral ligaments and reduces the displacement force of the intrinsic muscles on the proximal fragment, which facilitates stabilization. Repositioning the extensor tendon distally also results in about two-thirds of the proximal phalanx being covered by the extensor mechanism, which contributes to fracture stabilization [5,10,11]. After extra-articular K-wire fixation, the K-wire does not pass through the proximal IPJ (PIPJ) or MCP joints, allowing for joint movement while retaining the implant. To prevent adhesion, a limited active range of motion within the splint is started immediately after surgery, progressing to physical therapy approximately 3 weeks postoperatively, as the bone heals. Finger radiographs were acquired weekly after surgery to monitor bone healing. The K-wire was removed 4 to 6 weeks after surgery, based on achieving radiologic bone union and considering the clinical sign of tenderness loss along the fracture line, followed by splint removal. Subsequent ongoing physical therapy and self-exercises restore the previous range of motion.

Outcomes are periodically assessed using plain radiographs to identify proper bone union, malunion, or nonunion. The criteria for bone union encompass the disappearance of the fracture line, bridging callus formation, and periosteal thickening at both sides of the fracture [12]. We compared the timing of these criteria between the groups with antegrade and retrograde fixation.

Total active motion (TAM) and the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ) were applied to determine clinical outcomes and complications such as pin loosening and pin track infection associated with the fixed K-wire during pin dressing, stiffness, extension lag, and postoperative malrotation. Stiffness was defined as a condition where the total active range of finger motion is less than 80% [13]. Extensor lag was assessed as a condition where the proximal IPJ does not fully extend during active extension and remains flexed at a certain angle. We measured TAM 1 year after surgery and calculated the sum of active flexion angles at the MPJ, PIPJ, and distal IPJ. These angles were then categorized as excellent (220°–270°), good (180°–219°), fair (130°–179°), and poor (<130°). The self-reported MHQ was applied 1 year after surgery to evaluate overall hand outcomes [14]. This survey covers domains such as overall hand function, daily activities, work performance, pain, aesthetics, and satisfaction. Each question in these domains is scored from 1 (very good) to 5 (very poor). These raw scores are then converted into a range of scores from 0 (very poor) to 100 (very good) according to a specific formula.

Our findings are presented as descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviation, range, counts, and ratios (%). Nominal variables between groups were compared using either a chi-square test or Fisher exact test depending on the size and distribution of the data. The normal and non-normal distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Student t-test and Mann-Whitney U-test, respectively. Values with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Among the 73 patients with extra-articular fractures of the proximal phalanx base, 29 and 44 were treated by antegrade and retrograde closed K-wire fixation, respectively; Figs. 2 and 3 show the cases of antegrade and retrograde fixation, respectively. The demographic analysis revealed a similar distribution across age and sex, with no significant differences between the two groups. The predominant cause of injury in both groups was falls, closely followed by sports activities and occupational accidents. Notably, the little finger was the most frequently injured site, and oblique fractures were the most common fracture type identified, indicating a similar injury pattern across both groups (Table 1).

Surgical intervention metrics, including the number of K-wires used and the duration of the surgical procedures, were comparable between groups. Similarly, the timeline for postoperative care, encompassing the interval to implant removal and the initiation of physical therapy, showed no significant variations across the two methods (Table 1).

The absence of nonunion or malunion determined by radiological follow-up indicated successful bone union. The average amount of time to radiological bone union was slightly shorter in the antegrade than in the retrograde group (4.78 weeks vs. 4.92 weeks). Radiological outcomes did not significantly differ between the groups (Table 2).

The overall complication rate was higher in the antegrade group than in the retrograde group, although the difference was not statistically significant (13.8% vs. 9.1%). Extension lag was the most common complication (6.9%), followed by equal rates of stiffness and malunion (3.4%) in the antegrade group. Stiffness was the most prevalent complication in the retrograde groups (6.8%), followed by extension lag (3.4%) without malrotation. The average TAM was 230.14° and 236.54° in the antegrade and retrograde groups and was rated as excellent at 89.7% and 93.2%, respectively. No outcomes in either group were rated as fair or poor. The MHQ scores were 99.61 and 99.75 in the antegrade and the retrograde group, respectively. None of the evaluated clinical outcome categories significantly differed between the groups (Table 2).

In this study, we compared the outcomes of antegrade and retrograde K-wire fixation for proximal phalanx base fractures. Our findings reveal that both techniques are equally effective in managing these fractures, with no significant differences in complication rates, time to bone union, or functional outcomes as assessed by the TAM and MHQ scores. Although these metrics are directly related to the outcomes, examining the anatomical aspects of each technique helps understand the mechanism of how they are related. This approach is crucial because the extent of soft tissue disruption caused by K-wire fixation significantly affects the outcomes [15].

From an anatomical perspective, retrograde fixation with K-wire risks affecting the extensor mechanism. Although it does not directly pass through the extensor tendon as in transarticular fixation, starting near the PIPJ can irritate the lateral bands that extend from the intrinsic tendon fibers and travel along both sides of the proximal phalanx, eventually converging into a triangular aponeurosis at the distal phalanx (Fig. 1). They play a role in the extensor mechanism alongside the central slip of the extensor tendon during finger extension. However, friction caused by retained hardware around these bands can limit the range of motion [16]. Therefore, starting slightly below the joint when fixing near the PIPJ is advisable to avoid the lateral bands. Additionally, repositioning might be necessary after confirming that the tendon is not obstructed by passive PIPJ movement.

A cadaver study [17] has found that antegrade fixation of the proximal phalanx often intersects several soft tissue structures near the MPJ, including the sagittal band, collateral ligament, and joint capsule. At least one structure adjacent to the MPJ is always involved, with the joint capsule being the most affected. Extensor tendon involvement is rare, occurring in only 1 of 36 patients (3%), suggesting minimal impact of antegrade fixation on the extensor mechanism. Although the ligaments adjacent to the MPJ are associated with joint stability, they do not play a direct role in finger movement like the extensor tendon. K-wire transgression of these structures does not significantly impact clinical outcomes [9,18]. Nevertheless, direct damage from K-wire penetration and its restriction on mechanical actions can lead to adhesion and stiffness, hence structural interference should be minimized [17].

Although K-wire placement might interfere more with the extensor mechanism of retrograde, than antegrade fixation, the clinical outcomes of both methods did not significantly differ. This suggests that friction with the lateral bands in retrograde fixation is insubstantial, or that effort to avoid friction during surgery has prevented a negative impact on clinical outcomes.

Both methods involved crossing the fracture line obliquely and predominantly using two K-wires for cross-fixation. In some patients, a single K-wire was employed when the fracture’s instability and displacement were minor enough that one wire could achieve sufficient stability. This approach also aimed to minimize unnecessary soft tissue damage caused by the K-wires. In all patients treated with either one or two K-wires, there was an absence of malunion and nonunion, demonstrating that they successfully achieved good quality reduction and adequate fixation rigidity. Additionally, the radiological findings showed that bones healed in both groups by approximately 5 weeks, with no significant difference. However, outcomes determined from X-ray images do not always correlate with clinical healing [19], necessitating the consideration of clinical signs like the absence of tenderness on the fracture line as well [20,21].

Traumatic forces and resultant bony deformities can damage nearby ligaments and capsules or cause minor hematomas even in closed fractures of the proximal phalanx base. Retrograde fixation avoids additional iatrogenic inflammatory responses in these soft tissue structures, as the K-wire does not pass through soft tissues near the MPJ. However, retrograde fixation can be more technically challenging than antegrade fixation. The starting point for retrograde fixation at the proximal phalanx head is narrower than the base, thus requiring a more acute insertion angle. In contrast, K-wire advancement can be easier during antegrade fixation if the MPJ is accurately located, as the fracture site is near the insertion point. Furthermore, since extensive advancement towards the proximal phalanx head is not necessary, this obviates the need for an acute angle to insert the K-wire.

Postoperative management including implant removal and initiation of physical therapy did not differ significantly between the two methods. However, postoperative discomfort experienced by patients might differ. The postoperative location of externally protruding K-wires differs between retrograde and antegrade fixation, being on the lateral side of the finger, and protruding dorsally from the hand, respectively. The protruding K-wire needs to remain for longer outside the skin due to bulkier soft tissue on the dorsum of the hand compared with the fingers. If not left long enough, postoperative swelling can cause it to become buried. As the swelling subsides, the protruding K-wire can become more prominent and irritate surrounding tissues, causing pain. Susceptibility to external stimuli means that the K-wire can be pressed or its position altered, which sometimes requires cutting it shorter. In contrast, minimal soft tissue changes with retrograde fixation lead to less discomfort and easier pin management. We were unable to statistically compare patient satisfaction through surveys, but patients often reported discomfort with antegrade, but not with retrograde fixation.

The retrograde method was utilized in 44 patients, surpassing the 29 treated with the antegrade method. Our institution’s hand surgeons showed a preference for the retrograde approach, not due to statistical data but based on empirical evidence suggesting a lower overall rate of complications and higher patient satisfaction. Experience has shown that the antegrade fixation method becomes more advantageous when manual reduction is challenging. In such cases, it is necessary to firmly grasp and pull the entire finger to maintain the reduction while advancing the K-wire. Therefore, inserting from the dorsum of the hand, the antegrade fixation method proved more convenient. Conversely, the retrograde fixation method is considered more suitable for elderly patients due to the simplicity of managing the pins. For obese patients, who have difficulty identifying anatomical landmarks on a bulky hand dorsum, initiating the fixation from the lateral side of the finger with the retrograde technique may offer greater ease.

One limitation of our study is the relatively small sample. A larger sample would have rendered greater statistical accuracy and objectivity to the comparison between the methods. Additionally, when compiling patients for the study, we gathered and compared patients with fractures that were treated by surgeons who used both methods. Outcomes of the same method could vary due to differences among surgeons, indicating that variations might be attributable to operator characteristics. Furthermore, our analysis did not consider how the shape of the fracture might influence the choice of technique, nor did it examine which techniques might offer superior mechanical stability for maintaining reduction. These factors also represent potential variables that could impact outcomes, highlighting the necessity for further research.

Both antegrade and retrograde K-wire fixation techniques afford equivalent outcomes for the surgical management of proximal phalanx base fractures. Surgeons have the flexibility to select the method they are most comfortable with, considering factors such as the complexity of the surgery and their personal experience. Additionally, the choice can be influenced by the potential for optimizing patient satisfaction and comfort.

Fig. 1.

(A) Anatomical structures around the proximal phalanx, with a focus on extensor mechanisms. The proximal phalanx is outlined with a dashed line. A and B indicate the insertion points for antegrade and retrograde Kirschner wire (K-wire) fixation, respectively. Blue lines and arrows show the paths and directions of K-wire advancement, respectively. CS, central slip; MPJ, metacarpophalangeal joint; PIPJ, proximal interphalangeal joint; IM, interosseous muscle; DA, dorsal aponeurosis; LB, lateral band. Image used with permission; courtesy of Makoto Tamai, MD, PhD, Director and Hand Surgeon at the West 18th Street Hand Clinic in Sapporo, Japan. (B) Radiographic demonstration of antegrade and retrograde K-wire fixation. A and B indicate the insertion points for antegrade and retrograde K-wire fixation, respectively. White lines and arrows show the paths and directions of K-wire advancement, respectively.

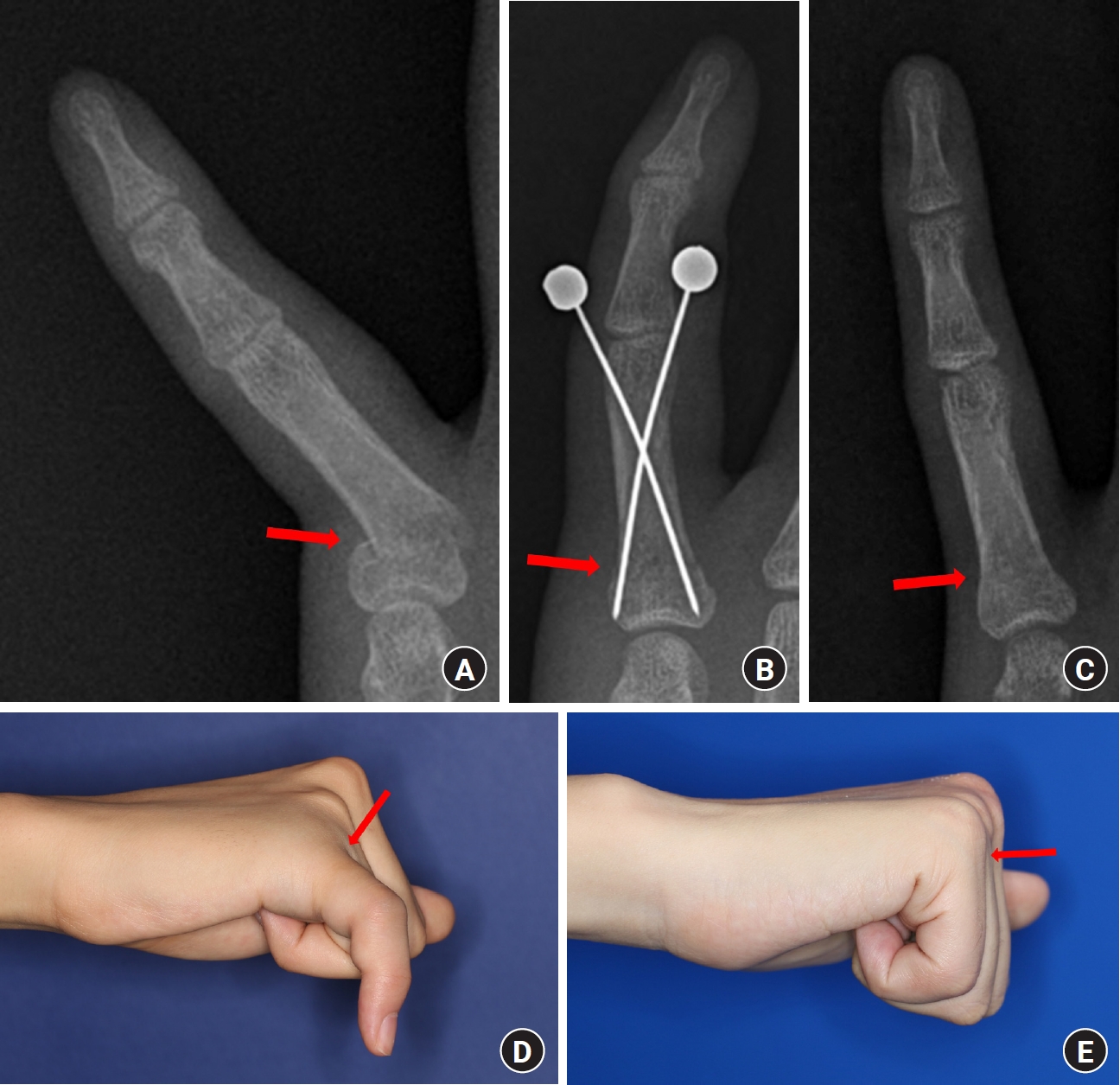

Fig. 2.

Radiographs of antegrade Kirschner wire fixation. Images were obtained before surgery (A), immediately after surgery (B), and at 1 year after surgery (C). (D, E) Range of motion before surgery (D) and 1 year after surgery (E). Arrows, fracture sites of the proximal phalanx.

Fig. 3.

Radiographs of retrograde Kirschner wire fixation. Images were obtained before surgery (A), immediately after surgery (B), and at 1 year after surgery (C). (D, E) Range of motion before surger (D) and 1 year after surgery (E). Arrows, the fracture sites of the proximal phalanx.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics, injury characteristics, surgical procedures, and postoperative management between antegrade and retrograde fixation

Table 2.

Comparison of radiographic and clinical outcomes between antegrade and retrograde fixation

References

1. Chung KC, Spilson SV. The frequency and epidemiology of hand and forearm fractures in the United States. J Hand Surg Am. 2001;26:908-15.

2. van Onselen EB, Karim RB, Hage JJ, Ritt MJ. Prevalence and distribution of hand fractures. J Hand Surg Br. 2003;28:491-5.

3. Ip WY, Ng KH, Chow SP. A prospective study of 924 digital fractures of the hand. Injury. 1996;27:279-85.

4. Windolf J, Siebert H, Werber KD, Schädel-Höpfner M. Treatment of phalangeal fractures: recommendations of the Hand Surgery Group of the German Trauma Society. Unfallchirurg. 2008;111:331-8.

5. Kozin SH, Thoder JJ, Lieberman G. Operative treatment of metacarpal and phalangeal shaft fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:111-21.

6. Singh J, Jain K, Mruthyunjaya P, Ravishankar R. Outcome of closed proximal phalangeal fractures of the hand. Indian J Orthop. 2011;45:432-8.

8. Belsky MR, Eaton RG, Lane LB. Closed reduction and internal fixation of proximal phalangeal fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9:725-9.

9. Faruqui S, Stern PJ, Kiefhaber TR. Percutaneous pinning of fractures in the proximal third of the proximal phalanx: complications and outcomes. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:1342-8.

10. Day C, Stern PJ. Fractures of the metacarpals and phalanges. In: Wolfe SW, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, editors. Green’s operative hand surgery. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2011. p. 239-90.

11. Rajesh G, Ip WY, Chow SP, Fung BK. Dynamic treatment for proximal phalangeal fracture of the hand. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2007;15:211-5.

12. Dijkman BG, Sprague S, Schemitsch EH, Bhandari M. When is a fracture healed? Radiographic and clinical criteria revisited. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24 Suppl 1:S76-80.

13. Onishi T, Omokawa S, Shimizu T, Fujitani R, Shigematsu K, Tanaka Y. Predictors of postoperative finger stiffness in unstable proximal phalangeal fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:e431.

14. Chung KC, Hamill JB, Walters MR, Hayward RA. The Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire (MHQ): assessment of responsiveness to clinical change. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42:619-22.

15. Horton TC, Hatton M, Davis TR. A prospective randomized controlled study of fixation of long oblique and spiral shaft fractures of the proximal phalanx: closed reduction and percutaneous Kirschner wiring versus open reduction and lag screw fixation. J Hand Surg Br. 2003;28:5-9.

16. Lögters TT, Lee HH, Gehrmann S, Windolf J, Kaufmann RA. Proximal phalanx fracture management. Hand (N Y). 2018;13:376-83.

17. Gordon J, Andring N, Iannuzzi NP. K-wire fixation of metacarpal and phalangeal fractures: association between superficial landmarks and penetration of structures surrounding the metacarpophalangeal joint. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2019;1:214-7.

18. Sela Y, Peterson C, Baratz ME. Tethering the extensor apparatus limits pip flexion following K-wire placement for pinning extra-articular fractures at the base of the proximal phalanx. Hand (N Y). 2016;11:433-7.

19. Dick H, Carlson E. Fractures of the fingers and thumb. In: Grabb WC, Smith JW, Aston SJ, editors. Grabb and Smith’s plastic surgery. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Company; 1991. p. 909-16.

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 53 View

- 2 Download

- Related articles in Arch Hand Microsurg

-

Temporary Intramedullary K-wire Fixation for Metacarpal Neck and Phalangeal Fractures2002 ;7(1)