Prevention of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema Using the Lymphatic Microsurgical Preventive Healing Approach: A Case Report

Article information

Abstract

Breast cancer-related lymphedema is a major complication of breast cancer surgery. The lymphatic microsurgical preventive healing approach, a surgical technique that can prevent breast cancer-related lymphedema, creates a lymphovenous bypass between the damaged axillary lymphatics during axillary lymph node dissection and the axillary vein. We report a case using the unilateral lymphatic microsurgical preventive healing approach in a patient with bilateral breast cancer. A 58-year-old woman diagnosed with bilateral invasive ductal carcinoma underwent a bilateral nipple-sparing mastectomy. The lymphatic microsurgical preventive healing approach was performed on the left side after axillary lymph node dissection; the lymphatic microsurgical preventive healing approach was not performed after axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy on the right side. Six months after the surgery, MD Anderson Cancer Center stage 2 lymphedema was observed in the lymphography images of the right arm, where the lymphatic microsurgical preventive healing approach had not been performed.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL) is a major complication of breast cancer surgery. BCRL results from obstruction or disruption of the lymphatic system, and the consequent mechanical insufficiency causes fluid accumulation in the interstitial tissues. This may bring about an array of problems, including significant physical, functional, quality of life, and economic problems [1]. The incidence of BCRL ranges widely, from 10% to 50% [2-4]. The most common risk factors for BCRL development include axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), regional lymph node radiation (RLNR), and having a high body mass index (BMI; >30 kg/m2) [5].

In recent years, lymphovenous bypass and lymph node transfer have been performed to treat BCRL, but these surgeries cannot definitively cure lymphedema, which has led to the development of methods to prevent BCRL. In 2009, the lymphatic microsurgical preventive healing approach (LYMPHA) was first described [6]. This technique involves creating a lymphovenous bypass between the arm lymphatics injured during ALND and the axillary vein. Many studies have reported that the incidence of lymphedema following LYMPHA after ALND is lower (4%–12%) than when LYMPHA was not performed [6,7].

Here, we report the case of a patient diagnosed with bilateral breast cancer who received LYMPHA on the left side following ALND and did not receive any prophylactic surgery on the right side after mastectomy and axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) for the prevention of lymphedema.

This report was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Hospital (No. 2106-036-104). Written informed consent was obtained for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old woman was diagnosed with bilateral invasive ductal carcinoma and was scheduled for surgical resection. The patient was scheduled for total ALND on the left axilla due to a prior positive axillary core needle biopsy and axillary SLNB of the right axilla. Thus, the patient was referred to our department for LYMPHA after ALND on the left side.

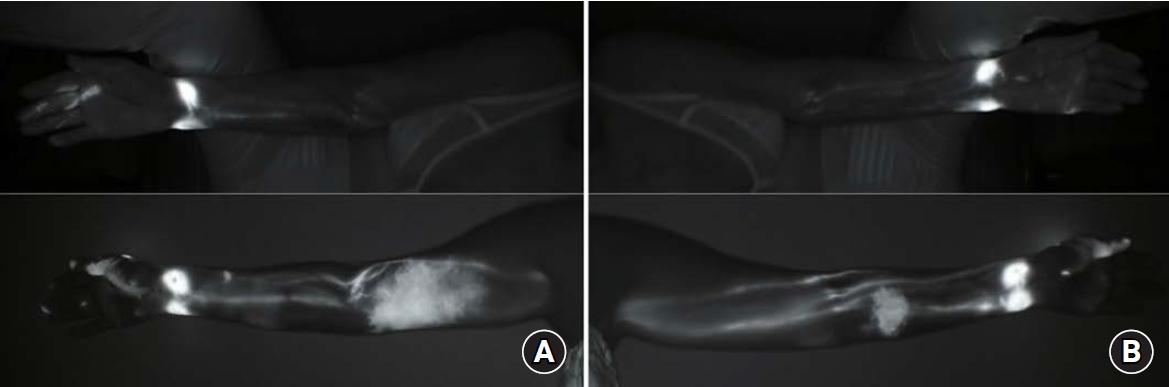

The patient’s BMI was 22.72 kg/m2, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy was not performed. To obtain baseline data, arm circumference measurements, lymphoscintigraphy using subcutaneous Tc-99m phytate injections into both upper extremities, and indocyanine green (ICG) lymphography were performed preoperatively. The measurements of both arms at three sites, including the wrist, 10 cm below the olecranon, and 10 cm above the olecranon, were measured using flexible tape. Based on arm circumference measurements, lymphoscintigraphy, and ICG lymphography, the patient had no preoperative lymphatic dysfunction (Figs. 1, 2).

(A) Photo of a 58-year-old female patient and (B) lymphoscintigraphy were taken preoperatively. Images were acquired 1 hour after administration of the radiotracer and show uptake at bilateral axillary nodes.

Indocyanine green (ICG) lymphography images taken (A) preoperatively and (B) 6 months after breast cancer surgery show MD Anderson Cancer Center ICG stage 2 lymphedema in the right medial upper arm where axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed. Dermal backflow is not observed in the left arm where lymphatic microsurgical preventive healing approach was performed after axillary lymph node dissection.

The patient underwent bilateral nipple-sparing mastectomy under general anesthesia for breast cancer. The weight of the resected breast was 490 g for the right side and 504 g for the left side. Twenty-one lymph nodes were removed through ALND on the left side. Four lymph nodes were taken for frozen biopsy on the right side, and the results returned negative; hence, additional surgery was not performed. During this process, axillary reverse mapping was not performed. Subsequently, LYMPHA was performed on the left axilla.

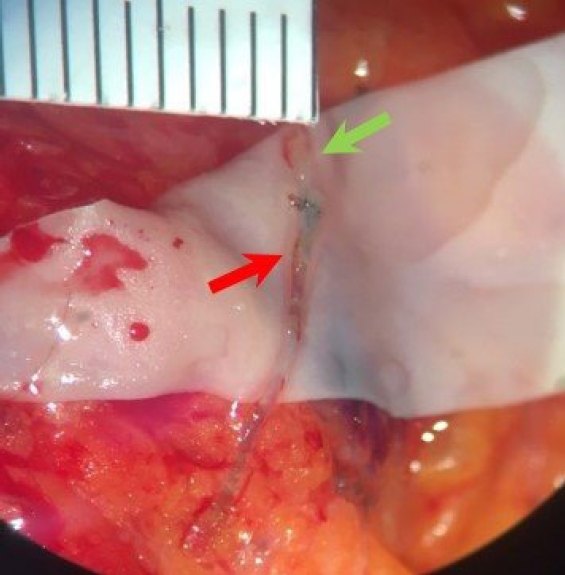

ICG of 0.4 mL was injected subcutaneously into the first and third web space of the hand and the medial and lateral borders of the volar surface of the wrist. The lymphatic drainage channel of the axillary site was visualized using an infrared camera (Moment K; Gils, Seoul, Korea). Based on lymphatic drainage channel flow, a total of 1 mL indigo carmine dye was injected into the intradermal layer of the upper third of the arm. We observed green-colored lymphatics draining from the arm. A 0.7-mm axillary lymphatic collecting vessel and 0.5-mm subdermal venule were identified; lymphaticovenous end-to-end anastomosis was performed with Ethilon 11-0 interrupted sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) (Fig. 3). Restoration of lymphatic flow was subsequently confirmed by wash-out and indigo carmine flow. Subsequently, breast reconstructions were performed with prepectoral implant placement on both sides (microtexture, round shape, BRMZ-M350, 350 mL; BellaGel, Hans Biomed, Seoul, Korea).

During lymphatic microsurgical preventive healing approach, lymphovenous end-to-end anastomosis was performed between the axillary lymphatics (red arrow) and a collateral branch of the axillary vein (green arrow).

Postoperatively, the patient received adjuvant radiotherapy on both the breast and left axilla. Patients were prescribed standard fractionation of 2.667 Gy per day to a total of 40.0 Gy and chemotherapy (four cycles of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide with four cycles of docetaxel). No physical therapy, compression bandage, or stocking was used after surgery. The patient was seen in our clinic at 2 weeks and 1, 3, and 6 months postoperatively.

Six months after the surgery, the patient visited the outpatient plastic surgery clinic because of mild swelling of the right arm. At the visit, circumferential measurements and ICG lymphography were performed. Arm circumference measurements confirmed a 2-cm difference between the right and left sides at 10 cm above elbow (Table 1). ICG lymphography images showed MD Anderson Cancer Center ICG stage 2 lymphedema (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

Various strategies to prevent lymphatic complications after SLNB and ALND during breast cancer surgery have been developed. Masià et al. [8] introduced a technique for lymph-lymphatic anastomosis after raising the flap containing lymph nodes during autologous breast reconstruction. In addition, Boccardo et al. [6] introduced LYMPHA, which involves performing lymphovenous anastomosis after finishing axillary lymph node excision to prevent disturbance to arm lymphatic flow caused by damaged efferent axillary lymphatics. LYMPHA is quicker and easier than lymph node or lymph vessel transplantation. Boccardo et al. [6] reported long-term follow-up results of 74 patients who underwent LYMPHA, and reported that only 4.05% of them developed lymphedema. Feldman et al. [7] reported that 12.5% of 27 patients who received LYMPHA had lymphedema as a result of a 3-month follow-up; whereas, 50% of 10 patients who did not receive LYMPHA developed lymphedema.

The prevalence of BCRL varies widely across studies. Several factors are related to this, and ALND, RLNR, and having a high BMI are known to increase the prevalence of lymphedema [9]. On the contrary, SLNB was performed to prevent lymphedema. DiSipio et al. [3] reported that the incidence of lymphedema in patients who received ALND was four times higher than in those who received SLNB. In addition, patients with primary asymptomatic lymphatic insufficiency may be more likely to develop lymphedema following oncologic interventions [10]. In the present case, dermal backflow was observed in the right arm for which SLNB was performed, while the left arm did not show BCRL, despite receiving ALND and RLNR. This difference can be attributed to performing LYMPHA on the left arm, and this case supports the idea that LYMPHA can lower the prevalence of BCRL.

Notes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by clinical research grant by Pusan National University Hospital in 2021.