|

|

- Search

| Arch Hand Microsurg > Volume 26(2); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Fingertip injury is one of the most common hand injuries. Although several types of advancement and cross-finger flaps exist, they would not be essential for nail bed defects. The authors present a simultaneous volar pulp and nail bed reconstructive technique that uses a second toe onychocutaneous free flap. Four patients without amputees underwent fingertip amputation reconstruction between 2011 and 2019. After thorough debridement, the defect size was estimated, and the digital arteries, nerves, and veins of the recipient were evaluated. The flap, composed of pulp tissue and nail bed, was harvested with continuity from the second toe. Additional split-thickness skin grafts were performed in two cases. All flaps survived without considerable complications. We evaluated the scar and contour, and nail growth was reported over Zook’s criteria grade B. The second toe onychocutaneous free flap provides a reliable option for fingertip defects that involve pulp tissue and nail bed without further amputation.

Fingertip injury is one of the most common hand injuries [1,2]. However, nail bed defect reconstruction is often considered negligible compared to that of volar pulp defects. Some types of fingertip reconstruction without further amputation are well known, such as the thenar flap, volar V-Y advancement flap, Kutler bilateral V-Y advancement flap, Moberg volar neurovascular advancement flap, and cross-finger flap; however, there are few reconstructive options for nail bed defects, except nail bed grafts. Therefore, nail bed grafting is necessary as a secondary operation after the generation of flaps for fingertip volume. In addition, these distinct surgeries are insufficient for maintaining the natural contour from the hyponychium to the volar pulp. We report a series of cases of simultaneous fingertip amputation reconstructive methods that use a second toe onychocutaneous free flap. The patient provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of his images.

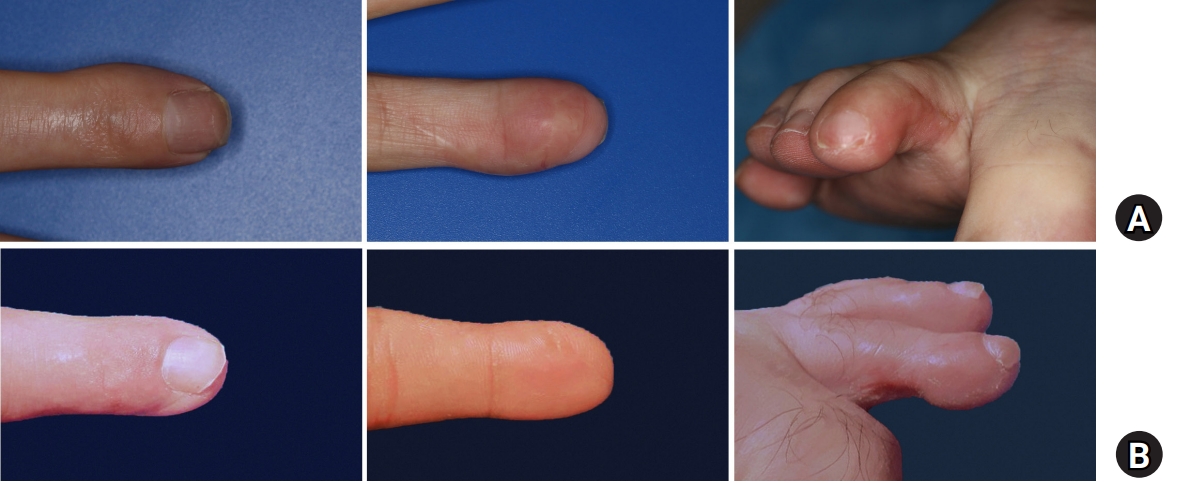

This surgery was performed for four fingers in four patients, between 2011 and 2019. They were all adults, three males and one female, with an average age of 29.8 years (range, 21–48 years). The surgeries involved three middle fingers and one index finger. All were crush injuries (one in a car wheel and three in a press machine) and Allen classification type 3 amputations with significant exposed distal phalanx and defects in the nail bed and pulp area (Fig. 1) [3,4]. Cases of pulp loss without nail bed defect or tuft bone loss were excluded. Two cases were performed under general anesthesia, whereas two cases were performed under regional anesthesia (brachial plexus block and spinal block) (Table 1).

The operation was undergone under tourniquet control on the thigh for the donor toe as well as on the upper arm for the recipient finger. This is for a moderate amount of exsanguination to secure visual field and better visibility of small volar subcutaneous veins. The full-thickness nail bed, pulp skin, the medial plantar artery, nerve, and the subcutaneous vein were harvested from the second toe. The vessels and nerve were connected to the digital artery, volar subcutaneous vein, and the digital nerve at the recipient finger.

Crushed nail bed and pulp tissue were adequately debrided after removal of nail plate of the injured fingertip with freer. The size of the defect is measured, and the digital artery, nerve, and subcutaneous vein were evaluated after Bruner’s zig-zag incision and careful dissection over the volar finger at the middle phalanx level.

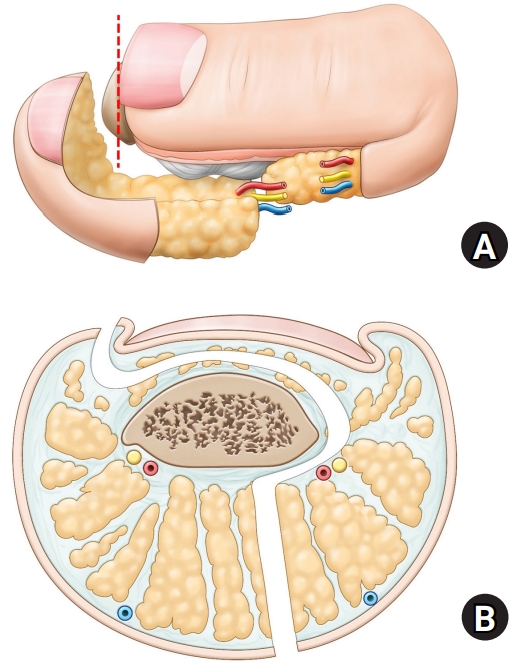

The donor—the tip and the medial side of the second toe—was designed with continuity. In addition, the zig-zag incision line was designed up to digitoplantar fold for a sufficient pedicle length. The flap incision should not cross the longitudinal midline except the nail bed and the tip for the complete closure of the donor. The incision line on the nail bed was designed again for precise incision after the toe nail is delicately opened with freer. The full-thickness nail bed was elevated first, and volar pulp was continuously dissected, up to subdermal level. Delicate dissection is required at the mid-level of the flap for preservation of the subcutaneous volar vein because it is usually located just under the dermal layer. If the veins are seen with ease, massage of the foot and the toe can help see them. In this way, one or two subcutaneous veins could be secured in the flap (Fig. 2A). After identifying the vein, the distal flap, the pulp tissue with nail bed, was dissected by dividing the vertical fibers around periosteum (Fig. 2B, 3B).

The tibial digital artery of the flap should be identified. Its landmark is the connecting branch with the fibular side of the digital artery at the level of the proximal part of distal phalanx [5]. This branch must be carefully cauterized, and the arterial pedicle is fully dissected to the level of the metatarsophalangeal joint for a sufficient pedicle length of more than 2 cm [5]. The circulation of the flap was identified by releasing the tourniquet on thigh, before the pedicle was disconnected. The donor site was primarily closed, followed by minimal bone trimming of tuft bone of the second toe.

The flap was transferred to the recipient and sutured around paronychium with nylon #5-0 and around nail bed with vicryl #6-0. The pedicle of the flap was inset to correlate to the neurovascular bundle of middle phalanx level of the recipient finger. One digital artery, one digital verve, and one subcutaneous vein were anastomosed in end-to-end fashion using nylon #10-0 (Fig. 2C). Two patients underwent split-thickness skin graft for the minor skin defect of the finger. Skin suture was performed on the flap with tension free for prevention of decreased circulation. After silicone sheet was inserted, moist dressing with short arm splint was applied.

After the surgery, patients had absolute bed rest with intravenous heparin 12,000 IU/day and alprostadil 10 µg/day for anticoagulation for 1 week. The heating lamp was also applied for the same duration. If the pain of donor site was tolerable, patients could walk in wards without any supplemental appliance. The short arm splint was removed within postoperative week 2. The physical therapy began, and the silicone sheet was removed on postoperative week 3.

The average flap size and length of pedicle were 2.90 cm2 (range, 2.76–3.00 cm2) and 2.38 cm (range, 2.2–2.5 cm), respectively. We evaluated the scar around the flap and shape of nail including donor site at final follow-up in the outpatient clinic (Fig. 4). The average follow-up duration was 9.25 months. All flaps survived with nail beds, and the wounds healed without any significant complications. The average prolonged nail was 3.75 mm (range, 3–4 mm) (Table 1). The nails of all patients did not have any other deformity such as nail ridge, split nail, and pterygium, and were graded as over grade B (very good) according to Zook’s criteria (Table 2) [6].

Fingertip injury is one of the most frequent hand injuries regardless of age [1,2]. If the amputee has clean-cut without contamination, replantation could be a better option. There are quite a few reconstructions that can be performed in accordance with the location, extent, and shape of injury in patients who are unable to be treated by replanting due to severe crush or amputation loss.

Skin graft or secondary healing can lead to wound contracture in the case of Allen type 1 amputation. A local flap or cross-finger flap is necessary for Allen type 2 transverse amputation, whereas a local flap or free flap is required for Allen type 2 oblique amputation [4]. When the level of injury is greater than that of Allen type 3, a local flap can close the open wound in some cases, but the free flap is absolutely needed in most cases [4,7].

Although the Atasoy volar V-Y advancement flap or the Moberg flap is mainly applied in case of transverse amputation over Allen type 3, the Moberg flap is difficult to be applied for other fingers except for thumbs [8,9]. The Kutler bilateral V-Y advancement flap is beneficial for central fingertip defect due to limited bilateral advancement. However, postoperative pain is one of the worst complications associated with fingertip scars [10].

These mentioned above are advantageous in that the normal sensibility maintains, any distant donor is not required, and they could be performed under the loupe magnification. However, they may not be essential reconstructive methods for nail bed defect. Indeed, patients with fingertip injury were worried about shortened nail and nail deformities as well as reduced fingertip.

Lee et al. [11] introduced a fingertip reconstruction in consideration of nail bed defects with a thenar fascial flap and subsequent nail bed graft. The thenar facial flap supplies multiple benefits—minimal donor site morbidities, maximal support for the nail bed graft, and nonmicroscopic surgery. Nevertheless, the reconstruction is largely the two-step surgery which requires a flap division and more recovery time.

The germinal matrix plays a significant role in most nail growth, while the sterile matrix makes the growing nail plate slide over [12]. Damage of the sterile matrix results in nail deformities, and scarred germinal matrix leads to nail absence [6]. The volar side of fingertip contains the critical small-sized cushion on which is one of the most sensitive sites. In these points, we propose that the onychocutaneous flap is another option for fingertip reconstruction in that there is no substitution of the nail bed.

This flap surgery demands the sacrifice of the second toe not as much as gait disturbances and surgeons’ microsurgical techniques. However, the second toe onychocutaneous free flap provides an essential method for nail lengthening by harvesting partial second toe pulp with a nail bed in cases of fingertip injury with nail bed defect. Moreover, it can create a more natural fingertip shape and prevent major nail deformities.

Fig. 1.

A 48-year-old female patient who injured her right middle finger visited our department without amputee. (A) Nail bed defect (dotted round) and bone exposure (arrow). (B) Volar pulp defect (dotted round) and bone exposure (arrow).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative photographs. (A) After dermal dissection, a digital artery (red arrow) and a subcutaneous vein (blue arrow) are seen at the med-level flap. (B) The flap is elevated on the anteromedial second toe tip, including nail bed and alongside the tibial side of the second toe. (C) The radial digital artery (red arrow) and a volar subcutaneous vein (blue arrow) are anastomosed at the middle phalanx level of the recipient finger. The radial digital nerve is anastomosed under the subcutaneous fat tissue.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram of flap harvesting. (A) The harvested flap from the second toe (red, artery; yellow, nerve; blue, vein). (B) Cross section view of the harvested flap. A red dotted line represents the cross section level in Fig. 3A.

Table 1.

Patients’ information associated with the surgery

Table 2.

Evaluation of nail bed reconstruction according to Zook’s criteria

| Criteria |

Case No. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Sex/age (yr) | Female/48 | Male/24 | Male/26 | Male/21 |

| Shape | ||||

| Identical | √ | |||

| Shortera) | √ | √ | ||

| Narrowera) | ||||

| Longitudinal curvea) | √ | |||

| Transverse curvea) | ||||

| Adherence | ||||

| Complete | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| ≥2/3a) | ||||

| <2/3b) | ||||

| Eponychium | ||||

| Identical | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Norcheda) | ||||

| Synechiaa) | ||||

| Surface | ||||

| Identical | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Slightly rougha) | ||||

| Very roughb) | ||||

| Longitudinal ribsa) | ||||

| Transverse groovea) | ||||

| Split | ||||

| Absent | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Presentb) | ||||

| Total | ||||

| Major | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Minor | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Grade | A | B | B | B |

REFERENCES

1. Cheung K, Hatchell A, Thoma A. Approach to traumatic hand injuries for primary care physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:614-8.

2. Satku M, Puhaindran ME, Chong AK. Characteristics of fingertip injuries in children in Singapore. Hand Surg. 2015;20:410-4.

3. Yorlets RR, Busa K, Eberlin KR, et al. Fingertip injuries in children: epidemiology, financial burden, and implications for prevention. Hand (N Y). 2017;12:342-7.

4. Spyropoulou GA, Shih HS, Jeng SF. Free pulp transfer for fingertip reconstruction: the algorithm for complicated allen fingertip defect. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;3:e584.

5. Lee DC, Kim JS, Ki SH, Roh SY, Yang JW, Chung KC. Partial second toe pulp free flap for fingertip reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:899-907.

6. Zook EG, Guy RJ, Russell RC. A study of nail bed injuries: causes, treatment, and prognosis. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9:247-52.

7. Appukuttan A, Ragoowansi R. The unilateral perforator V-Y flap for fingertip reconstruction: a versatile technique. JPRAS Open. 2019;23:1-7.

8. Atasoy E, Ioakimidis E, Kasdan ML, Kutz JE, Kleinert HE. Reconstruction of the amputated finger tip with a triangular volar flap: a new surgical procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:921-6.

9. Moberg E. Aspects of sensation in reconstructive surgery of the upper extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1964;46:817-25.

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- 3,032 View

- 75 Download

- Related articles in Arch Hand Microsurg

-

Subunit Principle: Key Element for Plantar Reconstruction with Free Sensate Flaps2021 March;26(1)

Onychocutaneous Flap: Fingernail Reconstruction with Arterialized Venous Free Nail Flap2005 ;10(3)

Salvage Reconstruction of the Knee using Latissimus Dorsi Myocutaneous Free Flap2002 November;11(2)

Bilateral Breast Reconstruction with Free TRAM Flaps2000 November;9(2)