하퇴부에 시행한 역행성 비복동맥 피판술 후 지연성으로 발생한 동정맥루: 증례보고

Delayed Arteriovenous Fistula after Reverse Flow Sural Island Flap in Lower Leg: A Case Report

Article information

Trans Abstract

Delayed arteriovenous (AV) fistula after soft tissue reconstruction with flap surgery is a rare complication. Here, we describe a case of delayed AV fistula formation after 4 years of reverse flow sural island flap surgery in the lower leg. The patient had swelling, tenderness, and color change to dark purple on previous flap area and foot, similar to cellulitis. Thrill and murmur were observed. AV fistula was formed around the previous vascular pedicle area, as revealed in angiography. We excised the right posterior tibial artery-saphenous vein fistula. The patient is having satisfactory progress since the surgery. We suggest that AV fistula was caused by enhanced angiogenesis and vascular damage.

INTRODUCTION

Delayed arteriovenous (AV) fistula after soft tissue reconstruction with flap surgery is a rare complication. To our knowledge, there are few reports of AV fistula that occurred after free flap surgery [1-4]. However, no cases of spontaneously developed AV fistula after island flaps have been reported. According to our knowledge, this report is the first to describe delayed AV fistula that occurred 4 years after a reverse flow sural island flap surgery in a lower leg.

CASE REPORT

A 46-year-old man visited the emergency room with open wound of about 10×5-cm size in the medial aspect of the right lower leg, which was hit by steel reinforcement in July 2011. Open segmental fractures of tibia and fibula classified with Gustilo type IIIB were diagnosed. Emergency operation was performed using external fixator in the tibia and Steinmann pin in the fibula (Fig. 1). Wound necrosis was aggravated and we performed reverse flow sural island flap. There was no difficulty in wound healing after flap surgery. After 1 month, external fixation was converted to internal fixation. The fractures showed complete union in the last follow-up, 2 years after the first surgery (Fig. 1). However, he visited our hospital and complained about pain on the right foot in May 2015. On physical exam, there was swelling and tenderness, color change to dark purple on the foot, and there was an ulcer on the midsole (Fig. 2). Initially, we assumed infection such as cellulitis or osteomyelitis. However, in blood lab test, infection markers including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and white blood cells were within normal range. Thrill was palpable around the previous flap area. On auscultation and ultrasound examination, a bruit was detected with the classical machinery-like murmur associated with an AV fistula around the previous neurovascular pedicle area and it disappeared when we compressed the proximal lesion (Fig. 3).

(A) Initially open fractures of the tibia and fibula were observed. (B) The fractures showed complete union in the 2 years after the surgery.

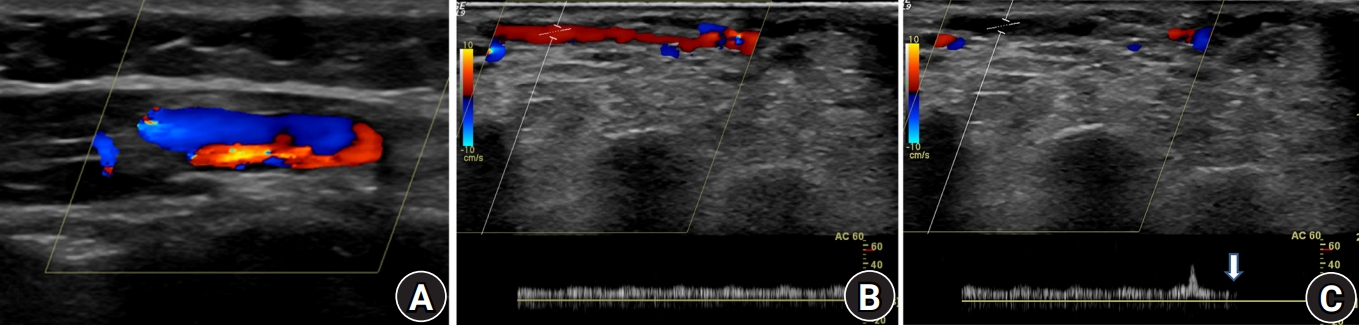

Ultrasound examination. (A) Arteriovenous fistula was detected around the previous neurovascular pedicle area. (B) A bruit was detected with the classical machinery-like murmur. (C) It was disappeared when we compressed the proximal lesion (arrow).

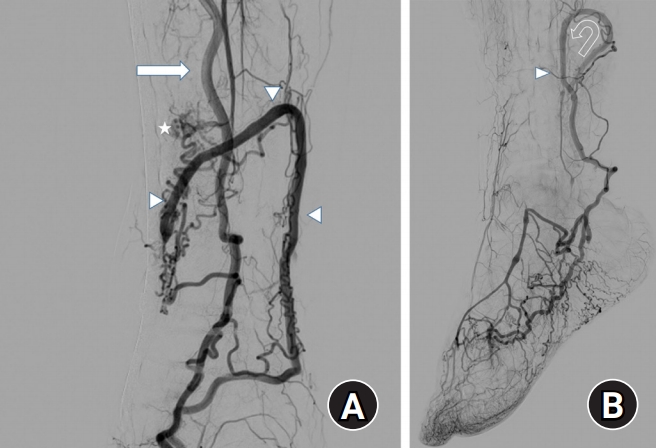

Three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) angiography and selective angiography revealed that some branches of the right posterior tibial artery were connected to the small saphenous vein around the flap. The small saphenous vein was dilated and its drainage was refluxed into the veins of the foot with multiple communicating vessels (Fig. 4).

Selective angiography. (A) In selective angiography, the posterior tibial artery (arrow) was connected to the small saphenous vein (arrowheads) and formation arteriovenous fistula (asterisk). (B) The small saphenous vein was dilated and its drainage was refluxed into (curved arrow) the veins of the foot with multiple communicating vessels (arrowhead).

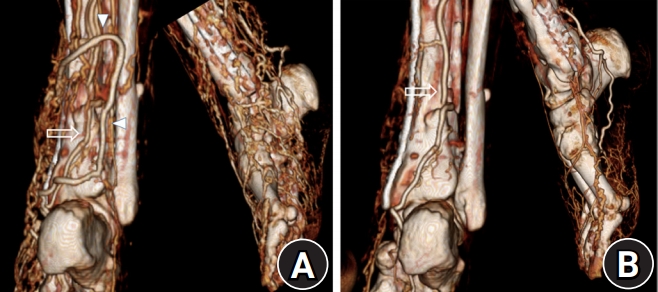

We decided to excise the shunt to decrease the hyperdynamic blood flow to the foot. Even though the AV shunt of the posterior tibia artery was temporarily blocked, we could confirm the blood circulation in the flap; therefore, we excised the AV shunt of the posterior tibia artery and saphenous vein. In immediate postoperative CT angiography it was revealed that the AV fistula disappeared and venous dilatation was decreased in the foot (Fig. 5). After 2 years of follow-up, there is no evidence of recurrence of the fistula so far, and the patient retained an asymptomatic foot, suggesting that the sural flap remains in situ and functional.

In preoperative computed tomography (CT) angiography and immediate postoperative CT angiography, arteriovenous fistula and the small saphenous vein were disappeared and venous dilatation was decreased (A), compared preoperative CT angiography (B). The posterior tibial artery (arrows), the small saphenous vein (arrowhead).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wonkwang University Hospital (No. 2020-10-037). The written informed consent to publish these case details was obtained from the patient.

DISCUSSION

An AV fistula is defined as a combination of arterial and venous injury at corresponding sites, creating a short-circuit connection between the two vessels without an intervening capillary bed [5]. The acquired AV fistula usually occurs due to iatrogenic trauma such as a puncture during percutaneous cardiovascular procedures [5].

AV fistula formation after flap reconstruction is a rare complication. Ninković et al. [1] reported an AV fistula that occurred 5 months after a lateral arm free flap to the extensor surface of a replanted hand. Maher et al. [2] reported an AV fistula after a free anterolateral thigh flap, while Collin et al. [3] described one after a free pectoralis minor flap for facial reanimation. Nikfarjam et al. [4] reported an AV fistula secondary to a debulking procedure with cross-clamping of the vascular pedicle of radial forearm free flap lesion.

Causes of an AV fistula formation after a flap surgery may be diverse, such as congenital dispositions, traumatic causes related to free flap transfer, long-term exposure to coldness, vasospasm, and predominance of arterial supply to venous drainage [6]. As the first hypothesis, we have assumed the cause of AV fistula formation could be traumatic injury that occurred during the flap surgery. Collin et al. [3] reported that an AV fistula can occur due to injury during vessel anastomosis. In our case, this was less likely because there was no vessel anastomosis. However, there might have been a vascular injury during dissection.

Moreover, we assumed that enhanced angiogenesis due to ischemic condition of flap lesion resulted in newly formed vessel with hemodynamic change. As a result, AV shunt developed through the abnormal communications for long time. Komai et al. [7] reported that angiogenesis due to capillary density induced vessel remodeling and this generated the AV shunt in rats. Mork et al. [8] reported that microvascular AV shunt was a probable pathogenic mechanism in erythromelalgia symptoms.

Early AV fistula formation in lower extremities is asymptomatic. However, chronic AV fistula can cause pain, swelling, pigmentation, ulceration, and necrosis. Pulmonary embolism and cardiac failure are also caused depending on the location and the size of the fistula. Therefore, early diagnosis is important. The diagnosis is made with the help of clinical findings such as thrill. However, the thrill may not be detected if there is an AV fistula in deep tissues [5]. Duplex ultrasound is a diagnostic tool for an AV fistula and offers the advantage of a noninvasive investigation. Angiography is needed to confirm the exact shunt site and overall condition.

Vascular interventions such as catheterization with coiling and embolization are minimally invasive [9]. However, in AV fistula that occurs after flap surgery, the vessels are often small and vascular interventions cannot be done. Surgical treatment should accurately identify and completely remove the AV shunt. In the present case, it was important to check the circulation of flap by temporary compression of the shunt vessels before complete removal of the vessels. Through this process, we could achieve both stability of flap function after the excision and improvement of the patient’s symptoms.

Notes

The authors have nothing to disclose.